It’s time for Robert Kotsmith and Michael Chmielewski to fess up. Time to come clean. Guys, don’t worry. We forgive you. The Statute of Limitations of high school foolishness has passed now, and we just want to know how you did it. We really don’t care anymore.

In the July 1955 issue of Popular Mechanics, Jim Collison writes about two high school juniors at Foley High School, Foley, MN, about 67 miles northwest of Minneapolis. These two young men managed to build a voice recognition home computer called The Thinker twenty years before the first Apple computer came out.

Another way to see this in context. Computer History tells us that, only the year before, IBM (a real computer manufacturer) had rented 19 of its 701 computers to big outfits like research labs and aircraft makers, at the cost of $15,000 per month. One programmer was able to make the 701 play checkers.

In other words, 1955 is the era of room-sized computers that no one can afford. Yet these seventeen year-olds managed to make a computer that cost $120 and could recognize the human voice.

The only telling moment in this story is when the writer says that “All these answers were ‘pumped’ into the Thinker in a briefing session before I started my ‘interview.’”

Does this mean that this agglomeration of junk parts and flashing lights was meant to demonstrate what computers might be like fifty years in the future? If so, that’s the only line indicating this. The rest of the article points to sheer smoke-and-mirrors, like this one: “The Thinker is built largely around the molecular theory of magnetism, the electromagnetic theory and the theory of electromagnetic induction.”

Where are these people now?

- Robert Kotsmith (still alive and living in Minnesota)

- Michael Chmielewski (?)

Other Foley MN students mentioned in the article but not part of The Thinker.

- Versal Cross (Appears to have died in 2007)

- Thomas Wildman

- Gordon Viste (Appears to be alive and living in Minnesota)

I would love to hear from anyone connected to this.

High-School Robots Learn the “Three Rs”

By Jim Collison

An electronic thinker a completely mechanical robot built by Robert Kotsmith, 16, and Michael Chmielewski, 17, high-school juniors at Foley, Minn., is passing exams of a factual nature that would stump any uneducated robot.

The machine, built during a period of 10 months at an estimated cost of only $120, understands and answers the human voice. The Thinker answers mathematical questions, gives data on current events and history, writes and even learns new facts it does not already know.

Even to persons well versed on scientific progress, this project seems astounding. Foley science instructor Alfred A. Lease says this of his students: “Their accomplishments would make some college graduates look on with envy.”

When I walked into the chemistry laboratory of Foley High School, Lease and the two inventors were putting the Thinker through its trial performance. It had just written its first word: m-a-r-c-h. This was the month in which it was completed. As I walked in, the machine was writing l-e-a-s-e, clearly, in nearly square letters, slanted slightly left, about an inch high.

“Ask it any question you like,” suggested the students.

The machine has three units: The main compartment, about six feet long, three feet wide and four feet high, contains the “brain”; the second unit holds the counting and spelling mechanisms, and the third houses the writing apparatus.

On the central brain unit are five switches and five warning lights to indicate which switch is on. These switches control the areas in which questions can be asked. Cube-root and square-root answers, each controlled from a separate switch, are given on the numbered unit. There is a switch for longhand writing and one for answering current events. The fifth switch directs multiplication answers.

On the number-letter unit, one dial points to numbers 0 to 9, to a period, and to Yes and No. Another dial points to letters A to W. The mathematical answers are given through this unit along with answers that are spelled out. In the writing unit a pen, hovering over a stack of paper, is held and directed by two metal “seesaw” fingers.

I asked the machine for the square root of 98. (In asking questions through a microphone worn about the neck, each inquiry must be prefaced with “Now . . .”)

“Now . . .” Lease ordered, “give me the square root of 98.” As he said this he pronounced the words distinctly and counted on his fingers. Pronunciation must be clear and syllables counted since inquiries must be limited to ten syllables.

Slowly the number dial pointed out the answer. First to 9. Then to the period. Next to 8, and then back to 9. That was the correct answer, 9.89. I asked for the square root of 177. Again, the correct answer: 13.3. All these answers were “pumped” into the Thinker in a briefing session before I started my “interview.”

I turned to current events. “Now . . . president after Harry Truman.” Slowly it spelled out e-i-s-e-n-h-o-w-e-r. I asked for the governor of Minnesota. It paused a few seconds—about 10 seconds are needed between the answers and wrote in those peculiar “drawn” letters, f-r-e-e-m-a-n. Correct.

That’s remarkable for current events, I though, but how would it do on history? I led off with, “Now . . . who won the world’s series last year?” That was too easy. It quickly answered, g-i-a-n-t-s. I decided to go back a few years and asked the robot, “Now . . . who was president after Monroe?” The machine wrote in distinct letters, a-d-a-m-s.

Can the machine reason? A simple test showed that it will not. I asked, “Now . . . will Red China attack Formosa?” There was no answer.

The final question during this first 20-minute “run” surprised me. As a special treat for me the boys had “briefed” it. “Now . . .” they asked proudly, “name the represented magazine.” Placing one word over the other, it wrote, p-o-p-u-l-a-r M-A-C-H-A-N-I-C-S.

They immediately noticed the error, and looked embarrassed. “Mechanics” was spelled wrong.

So the machine could make a mistake, I thought. But no, it was a mistake in briefing the Thinker, not the Thinker’s error. The machine spells phonetically. After they told it to spell “mEchanics” the spelling was correct.

Neither Lease nor the boys will tell exactly how the Thinker functions. The “magic brain” is still under wraps because of possibilities of patents. This much of an explanation is given:

First, the Thinker is a facsimile type of machine. It reproduces answers given to it, but can’t think for itself.

An audible word, signal or sentence is spoken into the mike and is carried to the central “nervous system” or “brain.” Here the question is acted upon and answered by relaying electrical impulses over wires to a receiving apparatus which changes the impulses back into intelligible answers.

It does not involve anything basically original. Lease, who advised the boys, stressed that “we make absolutely no claims of discovering any new scientific phenomena.”

It is unique because it applies old principles in a completely new and different way, according to Lease. He explained it this way:

“A professor once told me the only difference between an engineer and anyone else is that what takes others 100 hours to do, an engineer can do in one hour. About the same thing is the case here.”

The machine’s parts–mostly scraps–are worth about $120. The boys estimate their actual labor at 560 hours each. At a dollar an hour the total cost would run a little over $1000. It’s powered by regular household current, and uses about 200 watts.

The Thinker is built largely around the molecular theory of magnetism, the electromagnetic theory and the theory of electromagnetic induction. In other words, it is as simple as the common bar magnet, the electric motor, the electric generator and the transformer. It deals with inductance and inductive reactance, as applied in pulsating direct-current and alternating-current circuits.

The inventors emphasize that it is a completely “closed circuit” device, using no form of radio-type transmitter or receiver. The machine was originally designed to be a communications device rather than a question-and-answer-type machine. Its biggest value would be as a communicator, the boys believe.

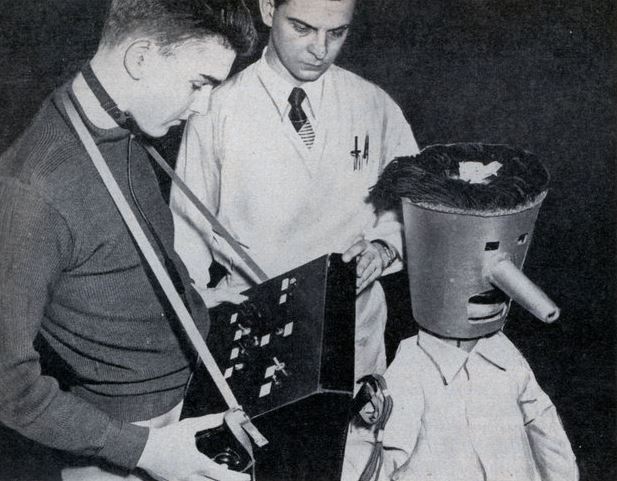

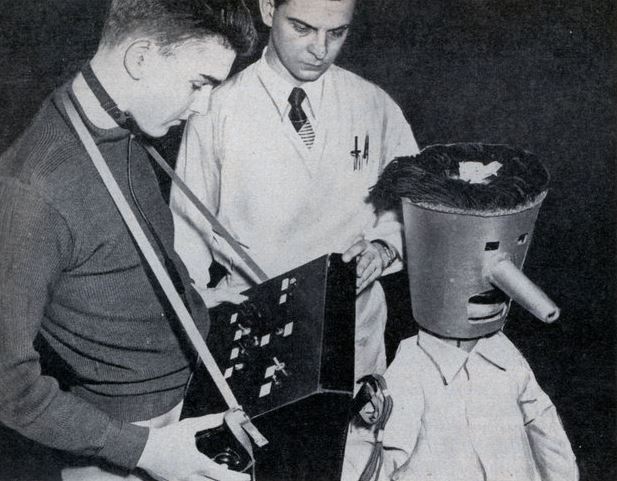

As a novelty, leaving the Thinker in the back room for a moment, Castor the Great steals the show. He’s a handsome, romantic and “dangerous” robot who roams the halls of Foley High School. Directing Castor on his jaunts is his creator, Kenneth Freude, 17, a junior.

After working for two months assembling various pinball-machine parts and other pieces of “junk,” Kenneth was able to make Castor walk, defend himself with a water gun, pick up paper, wink at girls, talk and react with fright by raising his hair! Total value of this project: about $200.

There is also a little robot. Versal Cross, 17, the senior student who built it calls it a Doodlebug or Snail. The Snail follows a beam of light and, having lost it, searches until it finds the light again. It is not controlled by radio or by other remote controls. Assembled, it looks like a giant bug with feelers guiding it as it searches for the beam of light.

Armies of the future might use cannons like the one Edward Heintze constructed as his science project. Loaded with water and a few drops of sulphuric acid, the cannon breaks the solution into gases. The gases are ignited by an electrical charge. With a loud “crack,” the cork is sent sailing across the 40-foot classroom.

For a more recreational project, seniors Thomas Wildman and Gordon Viste, both 17, connected an “electronic brain” to an electric train. A spoken command causes the train to stop, go forward or back up. The brain changes the sound waves of the voice into electrical currents. These are sent to the controls of a regular electric-train set. One “shot” of electricity stops the train, two shots make it back up and three shots cause it to move forward. When a series of syllables is said, either one, two or three, the same number of electrical shots enter the controls and move the train.

The train works just like an old Iron Horse, too. Using “whoa” for the one-syllable command, the train stops. “Get-e-up” will make it lunge forward. “Back boy” starts the train on a backward run. The more ordinary commands are “stop,” “go forward” and “back up.”

In every corner of this Foley classroom are student-built machines that perform a variety of tasks. Each student must work on one project a year.

Lease, who taught shop classes for two years before becoming science instructor last year, says, “I will feel lucky if my efforts help produce only a handful of scientists, for even this handful may be responsible in the end for keeping our country in the scientific lead.”