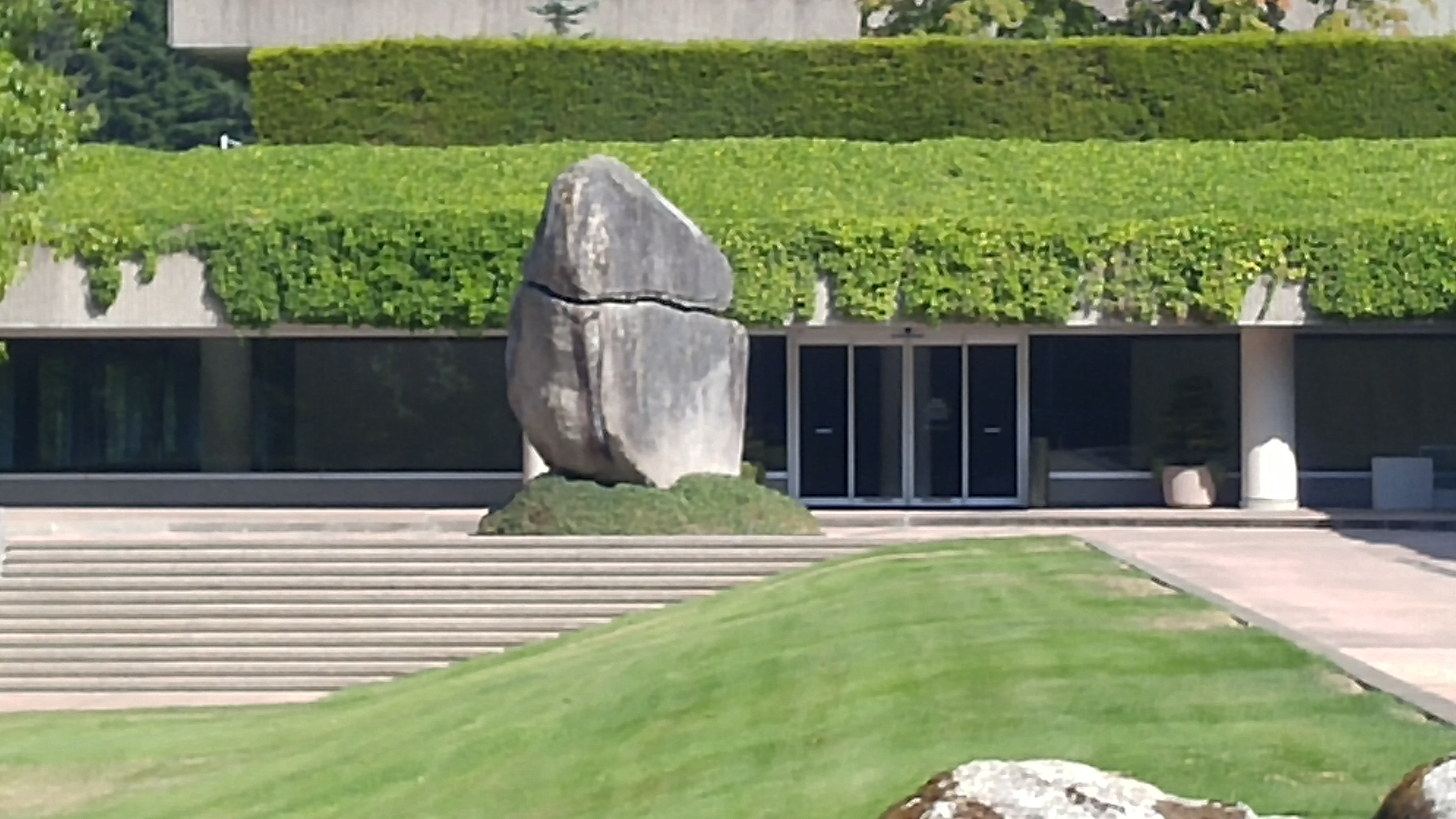

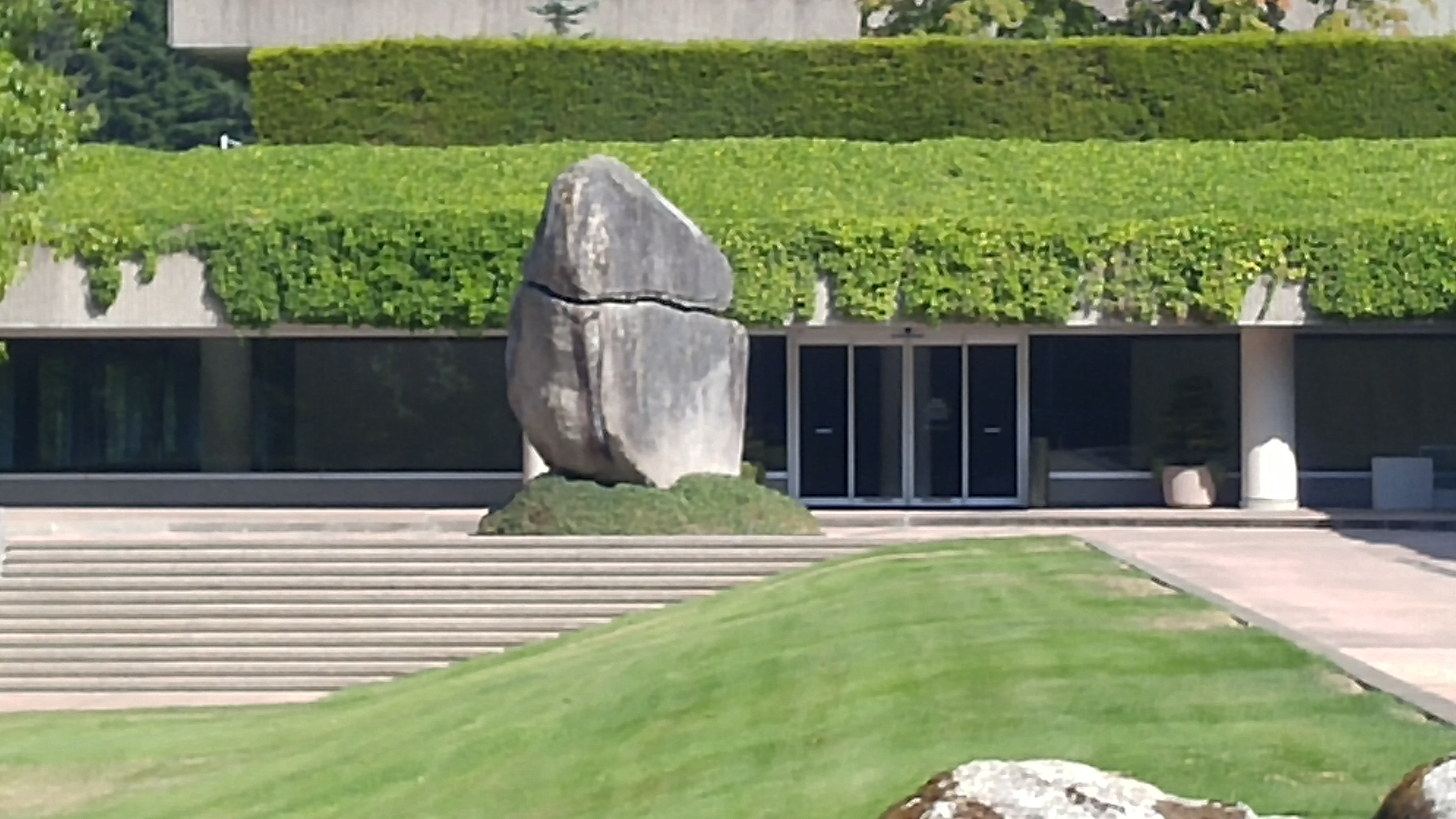

Quietly ensconced in 130 acres of woods south of Seattle is the abandoned campus of the Weyerhaeuser Corporation. Much like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, with gardens built into the walls of the palace, the Weyerhaeuser campus’ 5-story building is heavily draped with English ivy; thus the name of the complex: The Greenline.

Built in 1971 by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) architect Edward Charles Bassett, the complex is set into a hilly cleft and feels similar to Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1962 Marin County Civic Center. SOM calls the building a “groundscraper” or a “skyscraper on its side.”

In a 1992 interview, Bassett said of the complex:

The building has been one of my most satisfactory experiences. I wanted to find a point where the landscaping and the building simply could not be separated, that they were each a creature of the other and so dependent that they could hardly have survived alone. It’s a very simple statement, there’s nothing to it. Simply a number of terraced floors moving across from one side of a swale to the other. It’s a low ridge, so that you enter at the fourth level, a communal floor, with the three office floors below you instead of above. As the building progresses across the swale, forming a kind of dike or a dam, it gets broader as it goes on. The terraces are then planted with ivy that sweeps from the natural land form at either end. It’s elegant and understated and essentially un-architectural.

It was also the first example of the open office plan, with no walls between offices, only movable dividers (there were a few enclosed rooms for private conferences). Long before the green roof movement began, the Weyerhaeuser headquarters’ green roofs absorbed solar energy, directing glare and heat away from the inner office area.

In 2016, Weyerhaeuser abandoned the complex and moved into an uninspired glass building near Occidental Square in downtown Seattle. Today, The Greenline lies abandoned, crumbling, overgrown with ivy.